I recently read a story highlighting that Amazon sales

of George Orwell’s dystopian classic “1984” are up a whopping 6000 percent. It

seems that in the wake of the scandal parade that has been on the march through

Washington, highlighted by the NSA surveillance float, people have suddenly

found the cautionary tale of government power more relevant than ever. It

retains a certain tragedy that a novel published in 1949 about government

deception, manipulation and gross misuse of power has seemingly been used as an

instruction manual, lending it increased significance in 2013.

On that note, I’m convinced that if more people were aware of “All the King’s Men,” I think it would also experience a spike in public interest, owing to its timeless relevancy as a fable illustrating the fallout in electing a false idol into public office. Interestingly, “All the King’s Men” was released the same year as “1984” was published, and like Orwell’s classic novel, the film should serve as a good reminder that the means do not always justify the end, that government officials are not above the law and of the inevitable dangers in succumbing to demagoguery.

On that note, I’m convinced that if more people were aware of “All the King’s Men,” I think it would also experience a spike in public interest, owing to its timeless relevancy as a fable illustrating the fallout in electing a false idol into public office. Interestingly, “All the King’s Men” was released the same year as “1984” was published, and like Orwell’s classic novel, the film should serve as a good reminder that the means do not always justify the end, that government officials are not above the law and of the inevitable dangers in succumbing to demagoguery.

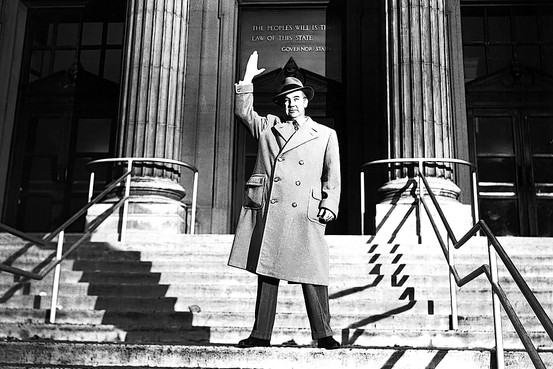

Directed by Robert Rossen, “All the King’s Men” picked up

seven Academy Award nominations, winning three, including Best Picture for

1949. Rossen also adapted the film from Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer Prize

winning novel of the same name, marking the last time a film with a Pulitzer

Prize-winning pedigree took home the Academy’s top honor. The film stars

Broderick Crawford, John Ireland, Mercedes McCambridge and other names not

likely familiar to modern audiences. But several of the lead performances are

unforgettable and still feel surprisingly contemporary, particularly Crawford,

who deservedly took home the Oscar statuette for Best Actor.

A roman-a-clef of the political career of former 1930s

Louisiana Governor Huey Long, “All the King’s Men” chronicles the rise and fall

of the fictional Willie Stark. A back-country hick inspired to take a stand

against the political slag polluting his town and county, Stark throws his hat

into the political ring of local government on a platform of truth and decency.

However, his message falls on the public’s deaf ears, mainly due to the fact

that the corrupt political machine has stuffed them full false promises and

deceit, preventing any alternative messages from ever registering on their

political consciousness.

Although realizing he has the charisma and determination to

win public office, Stark recognizes his lack of intellectual credibility,

spurning him to become a lawyer. After building up an account of public

goodwill through his legal practice, a political opportunity presents itself to

Stark after the local government’s corrupt practices finally bottom out,

resulting in the deaths of several school children. Angry and frustrated by

this tragedy, the general public urges Stark to run for political office,

marking his first step on a journey that would ultimately usher him into the

governor’s mansion. Stark’s journey ultimately recalls that quote from The Dark

Knight when Aaron Eckhart’s Harvey Dent presciently declares, “You either die a

hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain.”

Along the way, Stark becomes an almost Messianic figure to the common, less-educated voter, capitalizing on their ignorant follow-the-leader disposition by pied-piping a tune of hope and change. In the process, Stark quickly charters the same crooked course of the very politicians he railed against as an undereducated country bumpkin, emerging as a bruising political architect whose chief tools are intimidation, dishonest dealings and fear-mongering rhetoric. Arrogant and brash, Stark continually justifies his means by the ends he claims they produce, leading him to become sloppy, impudent and alienating toward those around him. Even when reality threatens to blow the lid off of his “accomplishments,” Stark only doubles down on his mistakes with a clenched fist, continuing to do everything he deems necessary in order to maintain his chokehold on the power he has amassed.

If “All the King’s Men” had a subtitle, I think a leading

contender for the spot should be “The Broderick Crawford Show.” He grabs the

part of Willie Stark with both hands, lowers the gas pedal to the floor and

doesn’t relent until the closing credits. It’s astonishing how Crawford is able

to subtly travel Stark’s trajectory, initially creating a portrait of a sympathetic

punching bag that you are rooting for to succeed. However, these sympathies

soon become distant memories once Stark yields to the trappings of power and

fame: carrying on with a merry-go-round of women; using and disposing of people

like snotty tissue; and even inflating his vanity with such indulgences as

wearing monogrammed house robes like some godfather figure. And what began as a

dream soon ends as nightmare, and by the film’s end you are rooting for this

erstwhile underdog to fail; as he is utterly remorseless in a way that leaves

you feeling used for ever having felt compassionate for him in the first place.

Crawford expertly guides Willie to this stage of his maniacal journey, mixing

up a cocktail of emotion that is tragic, frustrating and infuriating. It’s Crawford’s

talent at portraying struggle in paving the beginning of his own journey with

such noble intentions that allows his latter downfall to be received with such

complicated emotions. When Willie attains power to control the political

infrastructure and impose his will, Crawford’s performance generates a genuine

lament over the fact that he takes a jack hammer to the decent brick and mortar

that once surfaced his course. Ultimately, Crawford’s performance becomes a

great illustration of how absolute power corrupts absolutely, as they say.

If “All the King’s Men” had a subtitle, I think a leading

contender for the spot should be “The Broderick Crawford Show.” He grabs the

part of Willie Stark with both hands, lowers the gas pedal to the floor and

doesn’t relent until the closing credits. It’s astonishing how Crawford is able

to subtly travel Stark’s trajectory, initially creating a portrait of a sympathetic

punching bag that you are rooting for to succeed. However, these sympathies

soon become distant memories once Stark yields to the trappings of power and

fame: carrying on with a merry-go-round of women; using and disposing of people

like snotty tissue; and even inflating his vanity with such indulgences as

wearing monogrammed house robes like some godfather figure. And what began as a

dream soon ends as nightmare, and by the film’s end you are rooting for this

erstwhile underdog to fail; as he is utterly remorseless in a way that leaves

you feeling used for ever having felt compassionate for him in the first place.

Crawford expertly guides Willie to this stage of his maniacal journey, mixing

up a cocktail of emotion that is tragic, frustrating and infuriating. It’s Crawford’s

talent at portraying struggle in paving the beginning of his own journey with

such noble intentions that allows his latter downfall to be received with such

complicated emotions. When Willie attains power to control the political

infrastructure and impose his will, Crawford’s performance generates a genuine

lament over the fact that he takes a jack hammer to the decent brick and mortar

that once surfaced his course. Ultimately, Crawford’s performance becomes a

great illustration of how absolute power corrupts absolutely, as they say.

Of all the parallels this film draws with contemporary

Washington, perhaps the one that resonated with me the most is the correlation

between Willie Stark and our current political leadership’s refusal to ever own

up to a charge of real wrongdoing, a constitutional transgression or a grievous

error. Instead, the response is for D.C. to double down with heels dug in ready

to refute every accusation and deflect any consequence. I find the lack of

humility amongst today’s political elite to be truly stunning, particularly

when they are called in to answer for their crimes. It reminds me of the

oft-paraphrased scripture in Proverbs that says, “Pride goeth before

destruction, and a haughty spirit before the fall.”

Pride portending the fall is perhaps the core cautionary

theme coursing throughout “All the King’s Men,” which is perhaps what will

ultimately continue to make this film relevant for another fifty years. Unless

the voting classes wise up, the public sector will always be rented out to vain

hotshots who cocoon themselves within their own swollen doctrines. In that

climate, the Willie Starks of the world will continue to be elected with the

rest of regular society paying the price.

Favorite Line: At

one point during his gubernatorial campaign, Willie Stark is meeting with a

small gathering of elite society. Among them is a man by the name of Dr.

Stanton, who good-naturedly challenges Stark on how he proposes to fulfill his campaign

promises, which leads to the following exchange:

Stark: Do you know what good comes out of? Out of bad,

that’s what good comes out of because you can’t make it out of anything else.

Dr. Stanton: You say there’s only bad to start with, and

that the goodness comes from the bad. Who’s to determine what’s good and what’s

bad? You?

Stark: Why not?

Dr. Stanton: How?

Stark: It’s easy; just make it up as you go along.

No comments:

Post a Comment