Sunday, April 6, 2014

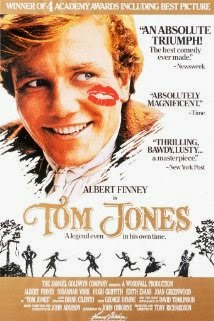

TOM JONES - 1963

Unfortunately, Tom Jones is not available on Netlfix. So I've elected to pass it over and continue moving on. Hopefully at some point down the road I'll have the means to watch it and add my riveting thoughts and insights to canon of those great critics of the past who have already weighed in on the matter.

Sunday, March 23, 2014

LAWRENCE OF ARABIA - 1962

I had never seen Lawrence of Arabia until viewing it for

this blog, despite being well aware of this film ever since I was a kid. My

grandma had a copy of it on VHS, spread across three videotapes, due to its

mammoth length. Needless to say, as a kid I chose to watch Ninja Turtles and

Pound Puppies instead. As for later on in life, I’m not quite sure why I never

got around to watching Lawrence of Arabia. There’s been nothing but ebullient

praise uttered on its magnificent behalf. Adjectives such as epic, masterpiece

and stunning have all become permanent fixtures in hailing descriptions of this

desert adventure. Given the fact that I haven’t watched it until now has

resulted in a lot of built up expectation for me over the years that this film

was going to be the cinematic equivalent of riding the lightening. After

becoming familiar with David Lean’s previous Best Picture winning effort,

Bridge on the River Kwai, I was expecting Lawrence of Arabia to be that much

more of a thunder punch of awesomeness.

So imagine my disappointment when the film turned out to be

just OK for me. I know that sounds incredibly snotty to say, bitchy even. But

it’s true, and I’m not going to deliver a bunch of canned praise

that isn’t sincere and genuine just because everyone else seemingly loves this

film. Actually, truth be told, Lawrence of Arabia’s first act had my complete

and full attention. But as the film wore on, my interest in the story and lack

of connection to the characters and their plight increasingly waned until my

mind basically checked into the classy establishment known as the “I Couldn’t

Give A Rat’s Ass” hotel. But I beg you, old sport, don’t misinterpret my

sentiment to be a confession that I detested the work in its entirety; quite

the contrary. There is a lot to admire about Lawrence of Arabia, and it is an

unquestionable achievement. But if a film delivers the razzle dazzle on all of

the senses save the heart, then it never truly delivers, which is the dilemma

Lawrence and I encountered together.

Directed by the terrific David Lean, Lawrence of Arabia is

toplined by Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins, Omar Sharif and the prodigiously

talented Peter O’Toole. Incredibly, the role heralded O’Toole’s film debut,

essentially making him an overnight sensation. The film also caused a sensation

among Academy voters, who wrapped the film in Oscar glory with 10 nominations,

and seven eventual victories, including Best Picture in 1962. In terms of Oscar

trivia, Omar Sharif’s nomination for Best Supporting Actor marked the first

acting nomination given to an actor from the Middle East (Sharif is from

Egypt). Additionally, the film marked the first of eight acting nominations for

Peter O’Toole, who, wickedly, was never awarded a competitive Oscar. Although,

the Academy did their best to make amends for this travesty by presenting

O’Toole with an Honorary Oscar in 2003.

Lawrence of Arabia follows an important chapter in the

military career of T. E. Lawrence, an enigmatic misfit lieutenant in the British

Army stationed in Cairo during WWI. Anxious to get out into the field, Lawrence

is offered an assignment to go and assess the prospects of Prince Faisal in

Arabia, and his campaign to put on his shit-kickers and revolt against the

Turks. This assignment marks the beginning of Lawrence’s later success in boldly

uniting the heretofore contentious tribes of Arabia in their struggle to

finally oust the Turks from their land.

Due to experiences in leading the guerilla campaign assaults

on the Turks, Lawrence gradually becomes a changed man, after waging and

suffering atrocities. He’s like the proverbial Jedi Knight who feels assured of

his place on solid ground, only to lose his footing and stumble into the realm

of the Dark Side. But what unnerves Lawrence the most is that he fearfully

discovers that he isn’t repulsed by unchaining his darker impulses. In fact, he

even relishes them to a degree. In the end, Lawrence is hailed a hero for

leading the liberation of Arabia from Turkey. However, the situation’s resolution

also signals the termination of Lawrence usefulness, and he is ordered to

return home in a state of dejection.

As I hinted at before, Lawrence of Arabia has many striking

features that make it difficult to refuse. The most salient component is the cinematography.

Stuh-ning. All of the desert vistas and rippling sandscapes are latitudinous in

scope and size. The scenes where Lawrence and his band cross the Nefad desert

is like an issue of National Geographic magazine’s greatest desert hits come to

life. I’ve never seen desert landscapes presented on film in such a domineering

and crushingly beautiful fashion. It truly created such an uncommon and

unfamiliar looking backdrop to the story that it produced the effect of being

otherworldly, as though David Lean had transported his entire cast and crew to

another planet. I’m conscious of the fact that it sounds like I’m over hyping

the visual splendor of this film, old sport, but I assure you that is not

possible. It’s a marvel and provides great merit to the film.

As I hinted at before, Lawrence of Arabia has many striking

features that make it difficult to refuse. The most salient component is the cinematography.

Stuh-ning. All of the desert vistas and rippling sandscapes are latitudinous in

scope and size. The scenes where Lawrence and his band cross the Nefad desert

is like an issue of National Geographic magazine’s greatest desert hits come to

life. I’ve never seen desert landscapes presented on film in such a domineering

and crushingly beautiful fashion. It truly created such an uncommon and

unfamiliar looking backdrop to the story that it produced the effect of being

otherworldly, as though David Lean had transported his entire cast and crew to

another planet. I’m conscious of the fact that it sounds like I’m over hyping

the visual splendor of this film, old sport, but I assure you that is not

possible. It’s a marvel and provides great merit to the film.

The other aspect pertaining to Lawrence of Arabia that

ignited my senses was the film’s score, composed by the brilliant Maurice

Jarre. I’ve loved so many of his other scores, such as Ghost and Doctor

Zhivago, but in my estimation, Lawrence of Arabia places as the crown jewel of

Jarre’s career. It’s exquisite and lush, with an elegant quality that swells in

its sonic capabilities. It all felt like a cool drink of water to the senses,

particularly during the sustained scenes in the desert. Thus far, I would rank

it second only behind Max Steiner’s work in Gone with the Wind on the list of

those most accomplished Best Picture scores. It adds so much emotion to the

film, preventing it from stumbling during the portions lacking in humanity and

depth.

But as I said earlier, a film can charm the senses, but if it fails in its effort to capture the heart, then it doesn’t truly succeed. I found this to be my dilemma with Lawrence of Arabia. It’s a great paradox: The film fired on all cylinders, yet failed to kindle an investment of feeling in the characters, particularly in the man himself: T.E. Lawrence. By the time the final credits unexpectedly roll, I felt as though I was meagerly any more attuned to understanding the character of Lawrence than when the film began. I get that he was an enigmatic character, I really do. But it seemed only thin strands of light filtered through to reveal his character, and in a film running nearly four hours long that is inexcusable. I felt as though the film hit all the right points in moving us through Lawrence’s adventure as it unfurled. But what of his disposition to join the tribes? The genesis to strike out into the desert to unite them? The origin of his short-lived streak of sadism? These questions and more rooted in the flesh of Lawrence’s character never really produce answers that can create any satisfactory dimension.

Clearly, Lawrence is a self-tortured man, but the complex

parts working in concert to produce his drives is never fully brought to bear.

One reason owing to this lack of illustration is that the film spends too much

time pulled back, showcasing the story on a more macro level. How can an

audience be expected to appreciate someone’s character when the story is more

wrapped up in sprawling scenery, exploding trains and arguments with commanding

officers? The simple answer is that they can’t. I’m convinced even the largest

personalities can’t compete against such entertaining splendor that the film

projects up there on screen, and T.E. Lawrence proves he isn’t up to the task,

either. The irony is that Lawrence of Arabia is, to a certain degree, a

character study, only except for the fact that no character is being fully studied.

In the end, it isn’t sufficiently moving, which left me feeling somewhat like

our hero, despondent in wondering what it was all for in the first place.

Clearly, Lawrence is a self-tortured man, but the complex

parts working in concert to produce his drives is never fully brought to bear.

One reason owing to this lack of illustration is that the film spends too much

time pulled back, showcasing the story on a more macro level. How can an

audience be expected to appreciate someone’s character when the story is more

wrapped up in sprawling scenery, exploding trains and arguments with commanding

officers? The simple answer is that they can’t. I’m convinced even the largest

personalities can’t compete against such entertaining splendor that the film

projects up there on screen, and T.E. Lawrence proves he isn’t up to the task,

either. The irony is that Lawrence of Arabia is, to a certain degree, a

character study, only except for the fact that no character is being fully studied.

In the end, it isn’t sufficiently moving, which left me feeling somewhat like

our hero, despondent in wondering what it was all for in the first place.

Favorite Line: In

speaking to Lawrence of his work with the Arabs and whether the British are

dealing openly and squarely with them, Mr. Dryden, his superior, tells him, “If

we've been telling lies, you've been telling half-lies. A man who tells lies,

like me, merely hides the truth. But a man who tells half-lies has forgotten

where he put it.”

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

WEST SIDE STORY - 1961

In many ways, West Side Story feels like a film shingled

with clichés and thin dialogue. I suppose the reason it feels this way is because

it is. It’s quite amazing, then, to consider that a film with these types of

blemishes should conquer its own imperfections to emerge so resoundingly

victorious on Oscar night. However, I think the explanation for this apparent

separation between perception and reality is really quite simple, old Sport:

The film’s music and choreography are so kinetic and irresistible that it pulls

the whole enterprise back from the brink, ultimately overshadowing and

minimizing the detrimental impact any negative traits might pose on West Side

Story.

Directed by the team of Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins, West

Side Story encompasses an eclectic gang of actors taking center stage,

including Rita Moreno, George Chakiris, Richard Beymer and Natalie Wood. In

addition to its large cast, the film also initiated 10 Academy Award statuettes

into its posse, from the 11 nominations it received. In terms of Oscar trivia,

West Side Story holds the distinction of being the musical with the most number

of victories, including the apex Oscar for Best Picture in 1961. Both Chakiris

and Moreno also took home the Golden Boys in the Supporting Actor categories,

paving the way for Moreno to eventually go on to become one of only four women

to have an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony victory to their credit, with Helen

Hayes, Audrey Hepburn and Whoopi Goldberg rounding out the distinguished

company.

Adapted from the 1957 Broadway smash, West Side Story is an

urban retelling of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Instead of Verona,

the fair scene is laid in a gritty section on the west side of Manhattan’s

claustrophobic asphalt jungle. And swapped out for two warring families, both

alike in dignity, are the Jets and the Sharks, two rival street gangs, both

alike in pride, angst and some resolute misdirection. The central feud is

territorial, with the Caucasian Jets lobbing accusations that the Puerto Rican

Sharks are trespassing on their concrete turf. Thus the two sides engage in an

escalating struggle to control the streets, punking and harassing each other

with a series of threats and minor skirmishes.

However, the stakes become significantly raised when Tony,

the leader of the Jets, falls hopelessly in love with Maria, the younger sister

of Bernardo, who is of course the leader of the Sharks. The star-crossed lovers

defy the street’s conventions, leading them to carry on a secret whirlwind

romance. But faced with the unalterable reality that a future together cannot

possibly flourish in their present environment, Tony and Maria make plans to

leave the west side in search of somewhere more accepting. In the meantime, their

forbidden affair has dialed up the heat between the Jets and the Sharks,

causing their hatred to collide and boil over, eventually spewing Tony and

Bernardo’s blood out into the streets and on to the hands of all those involved.

The glaring drawback of the paint-by-numbers parlance is

that it gives the film a distracting imbalance. The non-musical scenes feel

like moldy crusts of bread in comparison to the feast of musical sequences,

preventing the film from really rocketing into the stratosphere a truly great

films. To watch West Side Story feels like going for a ride on an open highway

that is littered with 25 mph zones and a lot of cops. The enjoyment of speeding

off into the horizon is tempered if the ride is frequently slowed down by

wooden dialogue and story development, so to speak.

Fortunately, the film spends the majority of its time with

its foot on the gas pedal, thanks in large part to the choreography spiking the

film with a nuclear, high-powered energy with destructive potential, which I

mean in a good way. All of the actors, whether they be principals or background

extras, leave blood on the dance floor, sometimes literally, infusing the film

with a spectrum of force ranging from spicy and cool, to rumbling and sweet.

Not that I’m some huge connoisseur of movie musicals, but I’ve seen my fair

share to the point that I feel confident in stating that the choreography and dancing

in West Side Story is unique and stylistically idiosyncratic in a way that

separates it from any other film with frolic. I think this unconventional

artistry is best exemplified after their big rumble with the Sharks; the Jets

have regrouped in a murky delivery truck garage to figure out their next step,

leading the gang into the number “Cool.” The choreography bubbles with

instability and irregularity, lending it an unpredictable nature. In a way, the

moves feel like jazz, in that there are all of these parts simultaneously

moving independent of one another, yet combining to create a marvelous spectacle

moving in subtle unison. Ironically, for a song about keeping it cool, real

cool, the number crackles and sweats with enough vitality to raise the dead.

Although, as great as the choreography is, I gotta say that

for me, basketball and ballet moves will never and should never be brought into

a mix together. Just like there is no crying in baseball, there are no ballet

moves in basketball. There just isn’t. I mean, you don’t see Kobe Bryant out

there doing a pirouette before taking the rock to the rack, do you? No. And you

want to know why? Because there is no ballet in basketball. I mean that settles

it.

But obviously, great choreography is nothing without great

accompaniment, and Leonard Bernstein and Steven Sondheim composed some

incredible tunes that inject West Side Story with snappy pulse, a broken heart

and youthful rage. It’s been ages since I last watched this film, and I had

forgotten what a hit parade of songs there are on the soundtrack, with recognizable

numbers like “Tonight,” “Maria” and “America.” It’s a testament to the music’s

enduring strength and catchiness that it has continued to live on all of these

decades later by permeating different avenues of pop culture, such as Saturday

Night Live, Mountain Dew commercials and even an Adam Sandler movie. It’s

fortunate for the film that the music is so dominantly memorable that it helps

to usher out the movie’s more lame or odd elements from one’s memory, as much

as it is possible to do so.

One odd element that lightly intersects with the narrative

of West Side Story is that it flirts with aspirations to be a pseudo-psychological

study, attempting to touch upon deeper themes of identity linked to cultural

transference, to belonging to a broken family and to being the product of a

society indifferent to at-risk youth. This is on full display during the number

“Gee, Officer Krupke,” as the Jets ridicule the failed attempts of the judicial

system to reform them of their ways, due to the system’s unwillingness to

understand them. In mock tones, the lyrics attribute their problems to being

the product of abusive homes with drug addicted parents and communist

grandfathers. These moments are peculiar detours that come off even more so in

the form of a musical presentation. I enjoy musicals, but I’m not entirely

convinced that it’s a format that lends itself to deep character development

and meaningful, sociological analysis. For musicals to work well, they tend to

have to move at a quicker pace, which typically results in a lean, condensed

narrative, not one that is conducive to performing a lot of heavy lifting. The

film sags whenever it tries to deliver some deeper commentary about societal

breakdown or the friction generated by tense race relations. Instead, West Side

Story is muscular when it is able to keep things simple, maintaining the

attention on the core conflict between the Jets and the Sharks. Fortunately,

for the most part it sticks to what it does best, making West Side Story an

overall strong film, but a sporadically weak one, as well.

Favorite Line: During

the number “Pretty,” Maria dreamily prances around the shop where she works,

singing about how pretty and wonderful she feels in the wake of falling in love

with Tony. At one point in the song, Maria declares, “I feel charming. Oh so

charming. It’s alarming how charming I feel.” This line makes me laugh because

it is so ridiculous and funny, making it the highlight of the film.

Wednesday, February 5, 2014

THE APARTMENT - 1960

For me, The Apartment is one of those films that conjured up

an overgrown reaction, forcing me to weed out my snap judgments toward the film

in order to be left with a more deeply rooted conclusion. At first, The

Apartment felt like one of those celebrated Best Picture winners that I just

couldn’t party down with. I couldn’t. I wouldn’t. Tonally, it felt like a

misfire; like some incongruent, slightly trashy fairytale that wields a lot of

effort into gussying itself up as this sweet rom-com. I found this distracting

because I feel like the film endeavored to make me laugh at a situation that

ultimately wasn’t funny. Sure, there are a few moments here and there that are

amusing enough old sport. But those amusements aside, The Apartment felt mainly

like a stocking stuffed with dark, corrupt and even tragic elements that left

me looking around to wonder if I was the only one in the room who didn’t think

this film is really all that tender and comedic.

For me, The Apartment is one of those films that conjured up

an overgrown reaction, forcing me to weed out my snap judgments toward the film

in order to be left with a more deeply rooted conclusion. At first, The

Apartment felt like one of those celebrated Best Picture winners that I just

couldn’t party down with. I couldn’t. I wouldn’t. Tonally, it felt like a

misfire; like some incongruent, slightly trashy fairytale that wields a lot of

effort into gussying itself up as this sweet rom-com. I found this distracting

because I feel like the film endeavored to make me laugh at a situation that

ultimately wasn’t funny. Sure, there are a few moments here and there that are

amusing enough old sport. But those amusements aside, The Apartment felt mainly

like a stocking stuffed with dark, corrupt and even tragic elements that left

me looking around to wonder if I was the only one in the room who didn’t think

this film is really all that tender and comedic.

Given the fact that my reaction to The Apartment was

seemingly the one boo among the sea of applause this film has garnered over the

decades, I decided to put my thoughts in a holding tank and circle back to it

during visiting hours. Not that I’m afraid to go against the grain of popular

opinion old sport. It’s not that at all. Instead, my reservation was more about

taking a cautious course of action in order to avoid being dismissive of

something that perhaps merited a little more analysis. Eventually, I found that

my initial reaction didn’t hold up after some more time and consideration,

leaving me to appreciate this film and some of the deeper themes that it

explored.

Directed by the wildly adept Billy Wilder, The Apartment

became his eighth and final nomination in the category of Best Director, which

he eventually went on to win, marking his second Oscar touchdown for directing

achievement along with The Lost Weekend, a full 15 years earlier. The marquee

tenants of The Apartment also include a young Jack Lemmon, an even younger

Shirley MacLaine and Fred MacMurray, playing so against type that I’m sure it

made Mickey Mouse almost hurl a Cadillac. The film hauled in an astonishing 10

Academy Award nominations, eventually renting out victories in the categories

of Best Art Direction, Best Editing, Best Original Screenplay, Best Director

and Best Picture for 1961. It was the last black-and-white film to win the Academy’s

top prize, until Schindler’s List owned the big night 32 years later. Also of note,

Kevin Spacey has said in interviews that he based his character in American

Beauty on Lemmon’s performance in The Apartment. In his acceptance speech for

Best Actor in American Beauty, Spacey dedicated his win to Lemmon, saying he

was “the man who inspired my performance. A man who has been my friend and my

mentor and, since my father died, a little bit like my father…. Wherever you

are, thank you, thank you, thank you.”

The Apartment centers on C.C. Baxter, a lonely, but eager

worker bee in a giant New York insurance hive with aspirations to buzz to the

top the corporate ladder. In order to hasten the ascension process, Baxter

enters into a deal, of sorts, with a cadre of scumbag company managers, lending

them the use of his Upper West Side apartment for their night-owl infidelities

in exchange for their recommendations of Baxter to the top brass for a

promotion. Eventually, the glowing reviews end up in the hands of Jeff

Sheldrake, director of personnel, who calls Baxter into his office to confront

him with the knowledge that he knows the cause of ignition driving his

colleagues’ enthusiasm. Instead of frowning upon such office corruption,

Sheldrake wants in on the action, agreeing to promote Baxter for the exclusive

rights to use his apartment for his own extra marital ring-a-ding-ding.

The Apartment centers on C.C. Baxter, a lonely, but eager

worker bee in a giant New York insurance hive with aspirations to buzz to the

top the corporate ladder. In order to hasten the ascension process, Baxter

enters into a deal, of sorts, with a cadre of scumbag company managers, lending

them the use of his Upper West Side apartment for their night-owl infidelities

in exchange for their recommendations of Baxter to the top brass for a

promotion. Eventually, the glowing reviews end up in the hands of Jeff

Sheldrake, director of personnel, who calls Baxter into his office to confront

him with the knowledge that he knows the cause of ignition driving his

colleagues’ enthusiasm. Instead of frowning upon such office corruption,

Sheldrake wants in on the action, agreeing to promote Baxter for the exclusive

rights to use his apartment for his own extra marital ring-a-ding-ding.

In the midst of tiptoeing through his corporate climbing

scheme, Baxter manages to siphon off enough time to make lighthearted attempts at

winning the attention of Fran Kubelik, a slightly sassy elevator operator working

in his same building. She finally agrees to a date with Baxter to go and see

The Music Man on Broadway, first telling him that she has to meet a former

flame for a quick drink. The old flame turns out to be none other than Baxter’s

new boss, Jeff Sheldrake, who manipulates Fran into believing that he

practically has the divorce papers all drawn up and ready for Mrs. Sheldrake to

sign. For weeks, Fran sort of dodges Baxter, buying into Sheldrake’s ever-growing

promises, until his secretary drunkenly spews out the truth to Fran that

Sheldrake is just dangling the pledge of divorce in front of her, with the

intent to eventually pull back once he is through with her. Angry and upset

with herself for being so foolish, Fran confronts Sheldrake at Baxter’s apartment,

before he leaves for the evening to be with his family on Christmas Eve. Alone

and despaired, Fran makes an attempt on her life by choking down an overdose of

jagged little sleeping pills.

Later that same evening, Baxter is shocked to discover Fran lights out on his bed, sending him frantically to enlist the help of a physician living next door. Eventually Fran recovers, recounting to Baxter the whole muddled yarn of her turbulent and foolish affair with Sheldrake. Ashamed and disgusted with his boss for manipulating someone he cares so deeply about, Baxter impulsively quits his job. Upon hearing this news, Fran tenders her resignation from her relationship with Sheldrake, arriving at Baxter’s apartment in time to stop him from moving out.

Later that same evening, Baxter is shocked to discover Fran lights out on his bed, sending him frantically to enlist the help of a physician living next door. Eventually Fran recovers, recounting to Baxter the whole muddled yarn of her turbulent and foolish affair with Sheldrake. Ashamed and disgusted with his boss for manipulating someone he cares so deeply about, Baxter impulsively quits his job. Upon hearing this news, Fran tenders her resignation from her relationship with Sheldrake, arriving at Baxter’s apartment in time to stop him from moving out.

One aspect of my reaction to The Apartment that has remained

constant is the terrific performances of its three leads. Jack Lemmon is aces

when it comes to playing the “every man” type of guy that audiences

instinctively find themselves rooting for. The Apartment is perhaps the best

example of Lemmon’s career that illustrates his ability to bring an effortless

and controlled goofy sensibility to a role. But a big part of Lemmon’s true

talent went beyond just being silly for the sake of drumming up some yuks. He

had this uncanny ability to nimbly walk the line of being funny without being

laughed at. As a result, he produced a genuine sweetness and likability that

elicited sympathy for his characters. With him, it felt like there was always

something more meaningful and more complex in the composition to the roles he

inhabited.

The Apartment created the perfect scenario for Lemmon in

allowing his particular set of strengths to shine through. As C.C. Baxter,

Lemmon brought the perfect blend of tenderness and naiveté to the part of

playing a guy who essentially gets in way over his head in pursuit of a

promotion. More often than not, Baxter is continually mishandling his affairs,

landing him in situations of being stood up out in the rain or with multiple

superiors at work breathing down his neck. It’s a delight to watch Lemmon

trudge home through the rain with a slumped posture or try and push back

against his superiors before caving in to their demands. He navigates these

scenes in such amusingly adorkable fashion that you can’t help but simultaneously

crack a smile and feel bad for the guy as he continually fumbles the ball.

The Apartment created the perfect scenario for Lemmon in

allowing his particular set of strengths to shine through. As C.C. Baxter,

Lemmon brought the perfect blend of tenderness and naiveté to the part of

playing a guy who essentially gets in way over his head in pursuit of a

promotion. More often than not, Baxter is continually mishandling his affairs,

landing him in situations of being stood up out in the rain or with multiple

superiors at work breathing down his neck. It’s a delight to watch Lemmon

trudge home through the rain with a slumped posture or try and push back

against his superiors before caving in to their demands. He navigates these

scenes in such amusingly adorkable fashion that you can’t help but simultaneously

crack a smile and feel bad for the guy as he continually fumbles the ball. Apart from Jack Lemmon, Shirley MacLaine also delivers the goods as Fran Kubelik, a romantically confused elevator operator continually finding the realities of her own love life shuffling up and down. As a result of her bad judgments regarding her affair with a married man, Fran has fallen toward the cusp of not believing in love anymore. Despite Fran’s congealing jadedness toward romance, MacLaine manages to prevent her from coming off as some bitter shrew stuffed with clichés, instead creating a sympathetic and charming gal who just needs to do a little growing up. Given Fran’s recent acquaintances with some of life’s harsh realities, MacLaine plays a slightly brassy, more serious counterpart to Lemmon’s goofiness, generating a sweet and innocent chemistry that hasn’t lost any of its appeal all these years later. For anyone who is a Shirley MacLaine fan, it’s worth watching The Apartment to see her play a softer, pixie-cute character before her career took a turn into her apparent specialty of playing harder-edged, more cynical women (Ousier, I’m looking in your direction).

But for my money, Fred MacMurray is The Apartment’s most

memorable tenant. I grew up watching him in all of those old Disney films like

The Shaggy Dog, The Absent-Minded Professor and The Happiest Millionaire. (Hell,

I still enjoy watching those movies even now that I’m into my thirties.) Maybe

it’s because he always played such likable characters, but for me, Fred

MacMurray is one of the most affable actors of all time. I think his talents as

an actor are heavily underrated. He was so adept at steering his characters

away from becoming caricatures of cantankerous old father types. Instead, he

managed to bring humor, insecurities, strengths, weaknesses and other

dimensions to characters that might otherwise have become wobbly creations in

the hands of lesser talent. I grant you that MacMurray rarely strayed from

playing a certain type of character, which makes his performance in The

Apartment so salient.

But for my money, Fred MacMurray is The Apartment’s most

memorable tenant. I grew up watching him in all of those old Disney films like

The Shaggy Dog, The Absent-Minded Professor and The Happiest Millionaire. (Hell,

I still enjoy watching those movies even now that I’m into my thirties.) Maybe

it’s because he always played such likable characters, but for me, Fred

MacMurray is one of the most affable actors of all time. I think his talents as

an actor are heavily underrated. He was so adept at steering his characters

away from becoming caricatures of cantankerous old father types. Instead, he

managed to bring humor, insecurities, strengths, weaknesses and other

dimensions to characters that might otherwise have become wobbly creations in

the hands of lesser talent. I grant you that MacMurray rarely strayed from

playing a certain type of character, which makes his performance in The

Apartment so salient.

To anyone who has seen Double Indemnity, the fact that

MacMurray could pull off a darker, more deviant role like Jeff Sheldrake

shouldn’t come as a surprise. And yet old sport, I’m here to tell you that it

still retained a certain shock to see MacMurray so effortlessly slip into the

skin of this manipulative and adulterous scumbag. All of that likability from

his tenure with Disney seemingly goes up in smoke after his first scene with

Shirley MacLaine where he is obviously stringing her along with a rat pack of

lies about leaving his wife and kids for her. But the real kicker is when he

threatens to fire Jack Lemmon after he initially refuses to loan him the use of

his apartment for any further rendezvous. MacMurray is so calm and pointed in

his unreasonable abuse of power during the scene, leaving you absolutely no

choice but to feel riled up. It really is just a great, modern villain of the

most despicable sort because at the end of the day his villainy is so miniscule

and nuanced in the grand scheme of things that in reality he’ll probably go on

stepping all over the little people until he retires. I think the main reason

MacMurray is so effective in this light, at generating such disdain and hatred,

is that he has built an entire career on playing the good guy. As a result, it

feels like some sort of a betrayal of trust to see him turn completely around

and reveal that he’s not that innocent.

As I mentioned in the opening paragraphs, my initial

negative reaction stemmed from the strange tonal dissonance created by the

film. On the one hand, the relationship between Jack Lemmon and Shirley

MacLaine positions the film to be firmly planted on rom-com soil. But I didn’t

buy this definition of the film at all. It felt like a salesperson trying to

sell me an item that is obviously something else entirely different from the

sale pitch. In this context, it seemed like Billy Wilder was trying to sell me

a bill of rom-com goods when in fact it was more in step with a sad-toned,

murky dramedy with suicide, corruption, deceit and adultery; elements that

don’t necessarily scream romantic comedy. But in reconsidering the events of

the story, I came to realize that the mixed message presentation was exactly

spot-on in how this story should be delivered. Essentially, the film evolves

from being a light-hearted comedy with some dark stains on it. As the film

progresses, those stains spread to overtake the light-hearted elements of the

narrative to create a situation of confusion. But by the time the final credits

roll, moral clarity has bleached away most of the blots, leaving a sense of

lucidity as to the direction of the film and its characters.

What does that all mean, exactly? Taken from Baxter’s

perspective, this tonal evolution is best explained by tracing his own personal

growth as an individual which illustrates how certain experiences can reshuffle

an individual’s list of priorities. In the beginning, Baxter is so focused on

getting that promotion that he is completely oblivious to the fact that he has

become an accessory to some pretty bad behavior that has ramifications in the

real world, particularly on his own character. It isn’t until Fran’s attempted

suicide is laid at his feet does he realize the despicable nature of the crowd

he now has a membership in. At this point, the darkness has edged out the light

and he has a difficult time seeing his way forward. Now that he has the job he

plotted and schemed for, he is disappointed to discover that it wasn’t worth

the price of selling out, leaving him in a confusing state of mind. Ultimately,

his self-sacrifice for Fran’s sake is what ushers in his regained sense of sure

footing in moving forward.

Ultimately, this final redemption is what made the film

redeeming for me. Admittedly, my strongest reaction against The Apartment is

that it felt like it was making light of adultery, which I straight up don’t

like. But in unpacking the story a little more, I came to the conclusion that

the film is touching upon deeper themes of blind ambition and office greed,

illustrating what happens when an individual allows them to seep deeply into

their consciousness. One effect is that one’s moral compass begins to spin in

every direction, which, when that happens, turns anyone into a master of

justification. I think this is why the film initially treats adultery like it

ain’t no thang but a chicken wang because Baxter has fastened on the moral

blinders in pursuit of his promotion. Fortunately, for his sake, Baxter is able

to pull himself back from the brink before his integrity is swallowed up for

good by the corporate monster.

Ultimately, this final redemption is what made the film

redeeming for me. Admittedly, my strongest reaction against The Apartment is

that it felt like it was making light of adultery, which I straight up don’t

like. But in unpacking the story a little more, I came to the conclusion that

the film is touching upon deeper themes of blind ambition and office greed,

illustrating what happens when an individual allows them to seep deeply into

their consciousness. One effect is that one’s moral compass begins to spin in

every direction, which, when that happens, turns anyone into a master of

justification. I think this is why the film initially treats adultery like it

ain’t no thang but a chicken wang because Baxter has fastened on the moral

blinders in pursuit of his promotion. Fortunately, for his sake, Baxter is able

to pull himself back from the brink before his integrity is swallowed up for

good by the corporate monster.

Favorite Line:

Jeff Sheldrake: Ya know, you see a girl a couple of times a week, just for laughs, and right away they think you're gonna divorce your wife. Now I ask you, is that fair?

C.C. Baxter: No, sir, it's very unfair... Especially to your wife.

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

BEN-HUR - 1959

Ben-Hur is nothing if not a colossal example of stirring, magnificent

pageantry. It’s that rare achievement where all the elements of film combine to

create a thundering spectacle that is truly unforgettable. It’s one of those

feats that raise the standard of filmmaking to such cinematic heights that few

films have been able to sustain a comparison to it without being swallowed up

by the shadow of its accomplishment. The signature chariot race alone is a

sequence few filmmakers could conceive, let alone actually pull off, even in

this time of advanced technology. But perhaps its greatest triumph is that the

intimate human drama and complex, internal struggle of its central character is

never trampled underneath the visually epic constituents of the film’s enormous

narrative. After watching Ben-Hur, it’s no wonder that Hollywood endeavors to

produce so few Biblical epics these days. In my opinion, it is one of the most

difficult genres to successfully navigate, particularly because producing success

in this arena takes faith, understanding and respect for religious-themed

subject matter, accoutrements which Hollywood has since long ago discarded.

Although I might be heating up a plate of crow in saying that, as 2014 is shaping up to be a year when

Biblical epics are poised to make a resurrected comeback, with big screen adaptations of

the stories of Noah, Exodus and Jesus all set for wide release. Whether or not

these efforts fail or flourish, it should be interesting to see Tinseltown’s

treatment of the Old and New Testament over the next several months.

Directed by the fearless William Wyler, and starring the

indomitable Charlton Heston, Ben-Hur dominated the 1959 Academy Awards with 12

nominations, taking home a record-setting 11 statuettes, including Best

Picture. The only other films to match Ben-Hur’s Oscar haul are Titanic and The

Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. The one category the failed to

realize Oscar gold was for Best Adapted Screenplay, which critics have

attributed to controversy over the film’s writing credit, which, if true, is

completely ridiculous. Pish posh on who actually wrote the thing?! The only

point that counts is that it was an incredible screenplay that should have been

honored regardless of who ended up taking home the bald guy that evening.

Through a series of fortunate events, Judah is able to save

the life of the Roman Consul Quintus Arrius amidst the chaos of battle with a

fleet of Macedonian ships. The Romans prevail in victory, resulting in Quintus

receiving credit for the campaign’s success. Grateful to Judah, Quintus adopts

him as his son and secures his freedom from slavery. Free from the shackles of

his sentence, Judah eventually returns home where he is given word that his

mother and sister have died in prison during his absence. Stung with hatred and

seething with an electrified vengeance in the wake of this terrible news, Judah

straight away seeks out Messala. As a side note, in the scene where Judah first

confronts Messala, who is stunned to see him return, it would have been awesome

in an over-the-top sort of way if Judah had turned to the camera and grisly said,

as only Charlton Heston can, “Ben-Hur’s back, bitch.” I guess that route was

deemed a little too irreverent, so instead, the story has Judah and Messala

settle their fates in a thunderous chariot race that leaves the latter mortally

wounded.

Through a series of fortunate events, Judah is able to save

the life of the Roman Consul Quintus Arrius amidst the chaos of battle with a

fleet of Macedonian ships. The Romans prevail in victory, resulting in Quintus

receiving credit for the campaign’s success. Grateful to Judah, Quintus adopts

him as his son and secures his freedom from slavery. Free from the shackles of

his sentence, Judah eventually returns home where he is given word that his

mother and sister have died in prison during his absence. Stung with hatred and

seething with an electrified vengeance in the wake of this terrible news, Judah

straight away seeks out Messala. As a side note, in the scene where Judah first

confronts Messala, who is stunned to see him return, it would have been awesome

in an over-the-top sort of way if Judah had turned to the camera and grisly said,

as only Charlton Heston can, “Ben-Hur’s back, bitch.” I guess that route was

deemed a little too irreverent, so instead, the story has Judah and Messala

settle their fates in a thunderous chariot race that leaves the latter mortally

wounded.  Before his wounds can carry off his spirit to the Great Beyond, Messala tells

Judah that his mother and sister are indeed alive (sort of), dwelling in the

Valley of the Lepers. Shocked by the news, Judah, grabbing the biggest bottle

of hand sanitizer that he can find, goes off in search of his leper family,

eventually reuniting with them under bittersweet circumstances. While trudging

along in the wilderness of his anger over the injustices suffered by his loved

ones, Judah comes to witness the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, whom he hears

preach about forgiveness while hanging on the cross. The words bring comfort to

Judah’s heart, allowing him to finally forgive the grievances brought against

him and his family and to move forward in peace.

Before his wounds can carry off his spirit to the Great Beyond, Messala tells

Judah that his mother and sister are indeed alive (sort of), dwelling in the

Valley of the Lepers. Shocked by the news, Judah, grabbing the biggest bottle

of hand sanitizer that he can find, goes off in search of his leper family,

eventually reuniting with them under bittersweet circumstances. While trudging

along in the wilderness of his anger over the injustices suffered by his loved

ones, Judah comes to witness the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, whom he hears

preach about forgiveness while hanging on the cross. The words bring comfort to

Judah’s heart, allowing him to finally forgive the grievances brought against

him and his family and to move forward in peace. It’s no great insight

to point out that everything associated with the Ben-Hur was ordered on a supremely

grand scale. The film’s running time is 212 minutes. The score is the longest

in cinematic history, requiring it to be spread across three LP records when it

was initially released for commercial purchase. Women in the Piedmont region of

Italy donated 400 pounds of hair to be used for wigs. The number of costumes

swelled to 100,000 different sets of attire, with the production of an

additional 1,000 suits of armor. The glorious chariot race scene used a set that

was constructed over 18 acres, using 1,500 hundred extras on any given day of

shooting. Upon completion of principal photography, over 1 million feet of film

had been used to capture the story of Ben-Hur, making it one of the most

monumental artistic achievements in the history of the world.

It’s no great insight

to point out that everything associated with the Ben-Hur was ordered on a supremely

grand scale. The film’s running time is 212 minutes. The score is the longest

in cinematic history, requiring it to be spread across three LP records when it

was initially released for commercial purchase. Women in the Piedmont region of

Italy donated 400 pounds of hair to be used for wigs. The number of costumes

swelled to 100,000 different sets of attire, with the production of an

additional 1,000 suits of armor. The glorious chariot race scene used a set that

was constructed over 18 acres, using 1,500 hundred extras on any given day of

shooting. Upon completion of principal photography, over 1 million feet of film

had been used to capture the story of Ben-Hur, making it one of the most

monumental artistic achievements in the history of the world. But when you can step back from the sheer size and depth of

the production, what is truly amazing about Ben-Hur is that the human drama and

the inner conflict are never eclipsed by the weighty spectacle. I think this is

due to the film’s exploration and illustration of the profound ideas rooted in

forgiveness, particularly in the face of engulfing injustice. This gives the

film a strong pulse that feels personal and real because everyone at some point

in their mortality is confronted with the decision of whether or not to show

forgiveness. In having to navigate the emotionally tumultuous journey that can

be presented in reaching a point where anger and vengeance are swapped out in

favor of forgiveness, Charlton Heston delivers a performance that feels

credibly dignified, tormented, aggressive and wounded. With the one-two punch of

playing both Moses and Judah, Heston’s talents seem specifically engineered for

these types of Biblical epics. He soars, where lesser actors would easily

plummet. He brings such a level of passion and earnestness to the character of

Judah that his suffering and joy feel unquestionably authentic and true. In

this light, it can rightfully be said that it’s Heston’s talent and strength that

lift the film into the leagues of greatness. The narrative revolves entirely

around the trials and tribulations endured by Judah, and Heston fearlessly

tackles all of the elements with confidence and zeal. So many films have proven

the fact that spectacle and thrills aren’t worth a damn unless they have real

characters and conflict to breathe life into them. Heston not only gave life to

Judah, and thus the entire film, but he completely electrified it with an

energy that still resonates more than 50 years later.

But when you can step back from the sheer size and depth of

the production, what is truly amazing about Ben-Hur is that the human drama and

the inner conflict are never eclipsed by the weighty spectacle. I think this is

due to the film’s exploration and illustration of the profound ideas rooted in

forgiveness, particularly in the face of engulfing injustice. This gives the

film a strong pulse that feels personal and real because everyone at some point

in their mortality is confronted with the decision of whether or not to show

forgiveness. In having to navigate the emotionally tumultuous journey that can

be presented in reaching a point where anger and vengeance are swapped out in

favor of forgiveness, Charlton Heston delivers a performance that feels

credibly dignified, tormented, aggressive and wounded. With the one-two punch of

playing both Moses and Judah, Heston’s talents seem specifically engineered for

these types of Biblical epics. He soars, where lesser actors would easily

plummet. He brings such a level of passion and earnestness to the character of

Judah that his suffering and joy feel unquestionably authentic and true. In

this light, it can rightfully be said that it’s Heston’s talent and strength that

lift the film into the leagues of greatness. The narrative revolves entirely

around the trials and tribulations endured by Judah, and Heston fearlessly

tackles all of the elements with confidence and zeal. So many films have proven

the fact that spectacle and thrills aren’t worth a damn unless they have real

characters and conflict to breathe life into them. Heston not only gave life to

Judah, and thus the entire film, but he completely electrified it with an

energy that still resonates more than 50 years later.

The other component that makes this a powerful and

compelling film is the portrayal of certain moments in the life of Jesus

Christ, his ministry and earthly mission, particularly the Crucifixion. The enactment is done with an undeniable

sense of reverence, but the act itself unfolds with the nature of a dark

political deed done to extinguish any flicker of peace or hope of freedom

from the Roman Empire’s bondage. It's emotional and affecting as a stand-alone event within in the film. But it also lends gravity to Ben-Hur's central

theme of forgiveness: Jesus Christ set the ultimate example by expressing forgiveness towards the Roman’s for

their deeds against him while he was hanging on the cross. On that note, perhaps the overarching

reason that Ben-Hur is an untouchable film that is likely to never be matched

by any future Hollywood production is that it contains some of the greatest events

and most enduring truths in the history of mankind, which transcends awards,

entertainment value and time, making the film forever resonant.

Favorite Line: The film has several great lines that offer great insight into the true nature of life. But I thought the final lines spoken by Judah and Esther, his love interest, to be the most poignant.

Judah: Almost at

the moment He died, I heard Him say, "Father, forgive them, for they know

not what they do."

Esther: Even

then?

Judah: Even then.

And I felt His voice take the sword out of my hand.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)